WhatsApp is one of the most popular apps in Brazil, which is installed on 98% of mobile devices in the country. While SMS messaging may cost money, WhatsApp is free.

“We don’t say text me, we say ‘zap me.’ It’s very entrenched in Brazilian society,” said Camila Leite Contri, coordinator of the digital rights section at the nonprofit Brazilian Institute for Consumer Defence (Idec).

During the isolating months of the Covid pandemic, the app became an essential lifeline for people to stay connected to friends and family and for small entrepreneurs to make a living amidst a major social crisis.

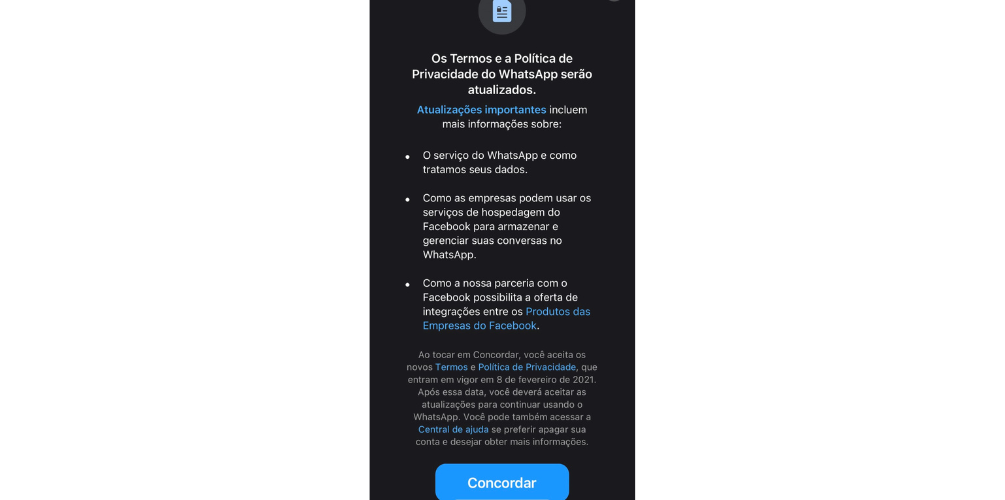

And it was at this moment, in January 2021, that WhatsApp gave Brazilians an ultimatum: Users must either allow WhatsApp to share their data with other Meta companies like Facebook, or stop using WhatsApp. This was a clear violation of Brazilian privacy laws.

Adding insult to injury, WhatsApp rolled out this privacy policy update differently in other parts of the world. In Europe, which has similar privacy protections as Brazil, WhatsApp complied with local regulations prohibiting data sharing between WhatsApp and other Meta companies after a decision held by the Irish Data Protection Authority in 2021.

In July 2024, Idec and the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office jointly sued Meta for over US$300 million for violating Brazil’s General Data Protection Law and the Consumer Protection Code. The civil action was the result of an administrative petition filed by corporate accountability watchdog, Ekō, in April 2021, to halt the policy. In August, a federal court issued an injunction blocking WhatsApp from sharing user data with other Meta companies and requiring WhatsApp to provide straightforward privacy choices. WhatsApp successfully appealed the injunction, but the legal battle will likely drag on for years.

Idec, Brazil’s premier consumer rights organisation, and Ekō co-led the legal and public pressure against this policy since 2021. Ekō also provided several groundbreaking legal analyses that formed the base of the civil action and an ongoing public pressure campaign. The case offers a paradigm for the way international and local civil society groups can pool their resources and expertise to curb Big Tech abuses of digital and human rights.

WhatsApp, the monopoly

In January 2021, WhatsApp users around the world began receiving a popup message. Flora Rebello Arduini was one of them. Living in London, she received a version of the popup modeled on the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). It offered her a button to accept the new policy and another to reject it. As a digital rights campaigner with Ekō, Arduini was interested in the policy change.

But her interest soon turned to alarm. In Brazil, where Arduini is from, the popup was different. Speaking with friends back home, she learned there was no button to reject the new privacy policy, a clear violation of Brazilian laws.

“I was outraged,” said Arduini, Ekō's Senior Tech & Human Rights Adviser. “Living abroad, I had more protection than my fellow citizens in my country, where a similar law was functioning but Meta decided not to respect it — treating Brazilians like second-class citizens despite being one of their biggest clientele.”

Idec said several aspects of the privacy policy rollout were illegal under Brazilian law, including the coercive popup, the lack of clarity about what was changing (some pages were not even translated into Portuguese), and the unnecessary processing of user data to build ever-creepier and more detailed profiles of people by surveilling users across platforms.

“Why do Europeans have stronger data protection than us if they have a very similar data protection law?” said Leite Contri, who helped lead the lawsuit. “Our legal system was breached and Brazilian citizens were treated as second-class citizens. Our Data Protection Authority didn’t advance with the case, which had been stalled since 2022. That’s the moment we decided to take this civil action against WhatsApp.”

Collaborating to build a case

Idec knew that the first hurdle would be to persuade the public prosecutor to take up the case. Both Idec and Ekō contributed to an independent investigation by the Public Prosecutors' Office (MPF). In this process, Ekō took the lead on hiring an independent expert to draft a legal briefing on WhatsApp’s data protection violations.

“It was extremely challenging, because most law firms in Brazil have some sort of conflict of interest,” Arduini said. Meta had some form of client relationship with many of Brazil’s leading law firms specialising in data protection. “This is a known strategy for Meta. They do this in key markets and make it really hard for civil society and other parties to hire lawyers.”

But Ekō ultimately found an independent attorney and contracted the briefing, which cemented the case and, more importantly, left no doubt that a civil action was necessary. Ekō launched a petition gathering over 210,400 signatures globally, while Idec started its own Say No campaign.

A second legal opinion on the privacy policy, written by an academic expert and brought to the procedure by Ekō, was essential to the progress of the prosecutor’s investigation and the evidence of violations of users' rights. This led to the conclusion that it was necessary to take the case to the courts. Idec and MPF then combined their efforts to jointly bring the lawsuit.

“The critical piece is making sure that everyone — the media, regulators and government representatives — know that people care a lot about this issue,” said Emma Ruby-Sachs, Executive Director of Ekō. “That's one of the most important pieces Ekō provided — an outcry with messages, petitions and public communications. Then we backed that outcry up with smart legal analysis, some great educating of the media about the complexities of the issue, and advocacy with decision makers.”

Landmark data protection lawsuit

On 16 July 2024, Idec and the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office filed their lawsuit against WhatsApp, seeking 1.7 billion reais (currently over US$300 million) and demanding an injunction against Meta before trial that would block the company from sharing Brazilians’ personal data outside of WhatsApp and give users the right to opt out.

The lawsuit additionally names the ANPD, Brazil’s data protection regulator. While initially cooperative, the agency has since become secretive and hasn't continued to pursue the investigation, Idec said. They refused to provide information or documents about their WhatsApp investigation to Idec and even to the public prosecutors. The lawsuit seeks transparency and an explanation for their secrecy.

Lawsuits often seek multiple injunctions and expect judges to grant some and decline or modify others. But on 14 August, the federal judge issued an unprecedented ruling that granted every demand against WhatsApp, obliging the company to limit the sharing of personal data to other Meta companies and to create an accessible opt-out tool. The judge ordered WhatsApp to pay US$36,000 per day if it doesn’t comply with the injunction by November 12.

“I could feel that that moment was paradigmatic,” Leite Contri said. “It’s so hard for a judge in any case to fully concede injunction claims, especially a very technical one.”

The celebration was short-lived: Less than a month later, the Court of Appeals agreed with WhatsApp’s appeal and suspended the injunction, which allowed the company to continue its data practices pending the outcome of the case.

Closing the enforcement gap

The block on data sharing could be ultimately confirmed by a final ruling, which could be years away and will also likely be appealed by Meta.

However, the collaboration between Ekō and Idec is a reflection of the interconnected global rights ecosystem that is needed to take on multinational tech corporations. “Everything in our world is integrated now and our movement has to be as well,” Ruby-Sachs said. “An ecosystem is not a coalition. It's an integrated system where each organism plays their role and supports and engages with the survival of the whole.”

Leite Contri said she hopes the lawsuit will encourage civil society groups in other countries to push back against Big Tech in the courts. Often, she said, these companies seem to imply that privacy is the price to pay for innovation and that they can leave their market if the laws are too burdensome.

“Why are we facing these abuses when other countries get protection?” she said. “Yes, we do need innovation, but we don’t have to exchange our rights [for it].”

Related content

Potencia: The power of beyond-the-grant support

The African Media Ecosystem and Technology

Black Awareness Day in Brazil: Why we must boost political representation